Be Here to Love Me

I hear my dad’s voice at night, low and murmuring.

I enter the pitch black darkness of his bedroom and ask him what he’s talking about.

He says to me, ‘Come in, I’ll show you what I’m about to do.’ ‘Oh,’ I said, what are you about to do?’

He chuckles softly and says, in a voice that is so childlike it startles me:

“Catch a whole bunch of fish.”

I remember him telling me years ago how when he was young his dad used to catch fish with his bare hands to feed their family.

I can only imagine that in this moment, in the darkness of his room, he was a child again, and was reliving the moment

My father was the family historian, the scrap-booker, saving every single award,

cutting out every mention of me in our local paper, no matter how small.

He would laminate each of my accomplishments, eventually filling albums with tiny fragments of my life.

He framed thank you letters received for his work by happy clients, photos of himself with important people.

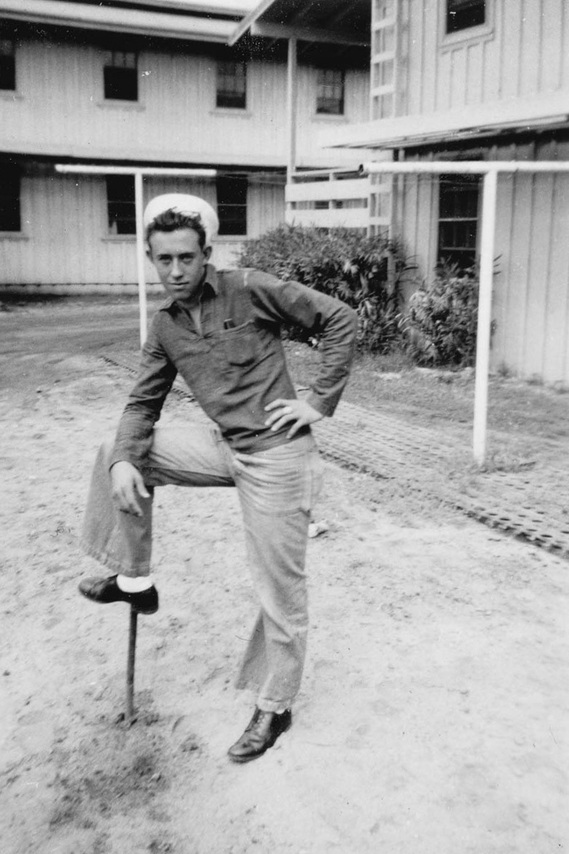

In a photo album he made of his time in the Navy Air Force,

he wrote on the back of many photos in which we appears, simply, the word ‘me’.

Sometimes I wonder if he knew somehow he would lose his memory and that’s why he was so careful to keep every piece,

every physical representation of his time on earth.

Sometimes I wonder if I, too, will get the disease and maybe that’s why I photograph.

Some of us may never know the secrets of our parents,

we die knowing them only as the thin paper cut out version that they wanted us to see.

Even before his dementia diagnosis, I knew my dad had a lot of secrets

Now, finally an adult myself, I'm mourning the time I wasted not asking him about his life,

when I was too young to be curious or care.

Dementia has been described as ‘an illness where the whole family gets the diagnosis.’

The nuances of the changing relationships that result from the disease are ever present, and the family unit is forever altered.

My mom mourns the loss of a person who is still physically present, yet absent in many other ways.

She is left to pick up the pieces of his fractured identity daily,

even in the act of answering questions, speaking for him,

and learning to live without the emotional support and intellectual stimulation he once provided.

Our relationship too, has shifted in dramatic ways.

We share something in loving my dad that only we know about.

It is the sadness shared between those who care deeply for someone struggling with disease.

Within all of this, the past, present and what’s real and imagined, live.

The very experience of dementia itself is one of erasure. A fogging of memory, a confusion of time and space.

But also, erasure of the Self.

How do you locate the personhood of someone

who is no longer the person you knew?

We fill in the holes with our own imagined or altered memories.

The space between metaphor and fact, performance and authenticity

Between the place where he is and the place where we are, looking in.

The image becomes a talisman that holds the power of our familial exchange.

The image is a way to heal.